Week 9: Digital History Reviews II - Mapping Early American Elections

Week 9: Digital History Reviews II - Mapping Early American Elections

Introduction

In order for elections to Congress during the First Party System to be mapped in a systematic way, it was necessary to gather the scattered election returns and then transform them into a dataset. Creating that dataset and maps is the aim of the Mapping Early American Elections (MEAE) project. Philip Lampi, leader of the parent project, A New Nation Votes, gathered election returns from across the country for over fifty years before it's digitization in the NNV project. Those election returns were then transcribed into XML files at AAS and Tufts and are hosted by the MEAE project. From their introduction, they draw the line showing how their project is not just a continuation of the work done by NNV, but how it gives new meaning to the data collected; Turning it from just transcripts, the main purpose of the MEAE project is to create data from digital transcripts and organize the data into a comprehensible format to provide a narrative of the early American Republic and their elections.

The Website: A Structural Analysis

The project (MEAE) has been operational since 2016 and carries a notable presence today since it's completion in 2019. From browsing the pages and hyperlinks, the site is in full functionality and doesn't seemed to have changed since the final blog post, officiating the project in 2019. Browsing it's creditors and sponsors, the page is supported directly by the the National Endowment for the Humanities and is continuously developed by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. In comparison to other projects, this website has surely been taken care of. Partially, I believe it's because of the care authors have done to maintain and engineer it, but also due to the sponsor and continued promotion of the site by national endowment groups over four years after it's original publication.

I observed their presentation of their inactive blogs, highlighting their step by step process over the three years of preservation and creation whilst the project was still active. The project leaders were sure to document findings and struggled as they mapped each decade of the continental congress and their respective votes. In comparison to other projects, authors like Greta Swain left small tutorials on how to access and review the maps to their full potential. It's a small addition, but it makes the project all the more accessible to those who wish to utilize it's narration. Not only did I find blogs showing each phase of the project, but they posted tutorials of their mapping software and how it can be replicated to create future projects along the same lines. For me, this is extremely interesting because it helps me further my own research implications and formats my mind to understand what is required of me before receiving` any sort of training in GIS specialties.

The Content: Data and Presentation

The content and presentation of the data is what originally drew me into this project. I ideally wanted to find a digital project that would semi, if not completely, model exactly what I wanted to do with my thesis and project component. As mentioned, MEAE's goal was to take previously archived transcripts and format them into tangible data that can not only be heavily analyzed, but also visualized in maps and charts.

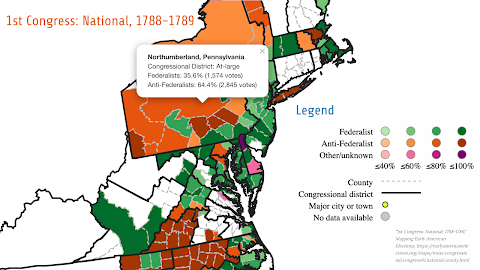

The site presents the work by categorizing the elections and rotations of the continental congress from 1788 to 1825 by dividing them by results of election by state, numbering each congressional formation. Each generation of congress is accompanied by a map of the general election, showing results from the state as a whole and maps describing the voting breakdown by county and population density. Maps are colored coded, accompanied by a legend describing the breakdown of party influence by county and city, showing the popular vote's choices in shifting tides.

At a closer inspection, I decided to reanalyze the blogs to further understand the dispersion, and most importantly, the handling of data. One blog post thats published to the site is titled What Did Democracy Look Like? Voting in Early America by Rosemarie Zagarri describes the nature of voting and how democracy looked in the early American republic. Zagarri highlights that democracy was more of a push-pull relationship between those creating laws and those wishing to find a voice in the ballot box. Due to the nature of ballot box, voting was more of a communal, public affair; Zagarri shows that the ballot box was an experimental approach to the understanding of the foundations and development of the American republican system (Zagarri, 2017).

I develop this idea as I analyze the development and expansion of the map over the 38 years of evolving American ideology. Not only does the size of maps grow due to American expansion to the West, the ideas surrounding how the common man was involved in the political construction of the early United States. The project does a fantastic job in the presentation and narrative showcasing of their work, truly providing a unique experience to the viewer's personal learning and research. I personally took a lot away from this project as it formatted my ideas surrounding my own future work with translating transcripts from documentation and translating them into readable, tangible data.

References

Mapping Early American Elections project team, Mapping Early American Elections, Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University (2019): https://earlyamericanelections.org, https://doi.org/10.31835/meae.

Comments

Post a Comment